Created 10.xii.19

Perhaps this post should be a post, or even an FAQ, in my CORE web site, but then I fear it would be taken too formally so it’s here. However, I’ll put a link to this from the CORE blog: this thinking started with one of a sudden slew of Emails I’ve had coming to me via the CORE site.

I won’t name names or Universities but I will say that it came from the UK. I think it could easily have come from other countries but I have the general experience that many countries still have less of this problem, seem less fearful of asking people about unhappiness or even self-destructiveness than many UK ethics committees seem to be.

The specific problem is the idea that if a research project asks people, particularly young people: teenagers or university students, about distress, and particularly about thoughts of self-harm or suicide, that there’s a terrible risk involved and the project shouldn’t happen. This sometimes takes the form of saying that it would be safer only to ask about “well-being” (or “wellbeing”, I’m not sure any of us know if it needs its hyphen or not).

A twist of this, the one that prompted this post, is the idea that the risk might be OK if the researcher using the measure, offering it to people, is clinically qualified or at least training in a clinical course. That goes with a question I do get asked fairly regularly about the CORE measures: “do you need any particular qualifications to use the measures?” which has always seemed to me to be about the fantasy that if we have the right rules about who can do what, everything will be OK.

This post is not against ethics committees. I have worked on three ethics committees and have a huge respect for them. They’re necessary. One pretty convincing reading of their history is that their current form arose particularly out of horrors perpetrated by researchers, both in the US and the UK, and also in the concentration camps. Certainly the US and UK research horrors did lead to the “Institutional Review Board (IRBs)” in the States and the “Research Ethics Committees (RECs)” in the UK. Those horrors that really were perpetrated by researchers, particularly medical researchers, but not only medical researchers, are terrifying, completely unconscionable. It’s clearly true that researchers, and health care workers, can get messianic: can believe that they have divine powers and infallibility about what’s good and what’s bad. Good ethics committees can be a real corrective to this.

Looking back, I think some of the best work I saw done by those ethics committees, and some of my contributions to those bits of work, were among the best things I’ve been involved with in my clinical and research careers so I hope it’s clear this isn’t just about a reasearcher railing against ethics committees. However, my experience of that work brought home to me how difficult it was to be a good ethics committee and I saw much of the difficulty being the pressure to serve, in the Freudian model, as the superego of systems riven with desires, including delusional aspirations to do good through research. I came to feel that those systems often wanted the ethics committee to solve all ethical problems partly because the wider systems were underendowed with Freud’s ego: the bits of the system that are supposed to look after reality orientation, to do all the constant, everyday, ethics they needed done.

In Freud’s system the superego wasn’t conscience: a well functioning conscience is a crucial part, a conscious part, of his ego. You can’t have safe “reality orientation” without a conscience and, as it’s largely conscious, it’s actually popping out of the top of his tripartite model, out of the unconscious. His model wasn’t about the conscious, it was about trying to think about what can’t be thought about (not by oneself alone, not by our normal methods). It was about the “system unconscious”: that which we can’t face, a whole system of the unreachable which nevertheless, he was arguing, seemed to help understand some of the mad and self-destructive things we all do.

In my recycling of Freud’s structural, tripartite, model, only his id, the urges and desires is unequivocally and completely unconscious, the superego has some conscious manifestations and these do poke into our conscious conscience, and the ego straddles the unconscious (Ucs from here on, to speed things up) and the conscious. (I think I’m remembering Freud, the basics, correctly, it was rather a long time ago for me now!)

I’m not saying that this model of Freud’s is correct. After all, Freud with theories, was rather like Groucho Marx with principles, they both had others if you didn’t like their first one …) What I am arguing, (I know, I do remember, I’ll come back to ethics committees and questionnaires in a bit) is that this theory, in my cartoon simplification of it, may help us understand organisations and societies, even though Freud with that theory was really talking about individuals.

As I understand Freud’s model it was a double model. The was combining his earlier exploration of layers of conscious, subconscious and Ucs with this new model with its id, superego and ego. They were three interacting systems with locations in those layers. With the id, ego and superego Freud was mostly interested in their location in unconscious. Implicitly (mostly, I think) he was saying that the conscious (Cs), could be left to deal with itself.

That makes a lot of sense. After all consciousness is our capacity to look after ourselves by thinking and feeling for, and about, ourselves. To move my metaphors on a century, it’s our debugging capability. Freud’s Ucs, like layers of protection in modern computer operating systems, was hiding layers of our functioning from the debugger: our malware could run down there, safely out of reach of the debugger.

The id, superego, ego model is surely wrong as a single metatheory, as a”one and only” model of the mind. It’s far too simple, far too static, far too crude. Freud did build some two person and three person relatedness into it, but it was still a very late steam age, one person, model and desperately weak on us as interactional, relational, networked, nodes, it was a monadic model really.

However, sometimes it fits! My experience on those committees, and equally over many more years intersecting with such committees, is that they can get driven rather mad by the responsibilities to uphold ethics. They become, like the damaging aspects of Freud’s model of the individual’s superego, harsh, critical, paralysing, sometimes frankly destructive. The more the “primitive”: rampant desire (even for good), anger and fears of premature death and disability gets to be the focus, the more they risk losing reality orientation, losing common sense and the more the thinking becomes rigid. It becomes all about rules and procedures.

The challenge is that ethics committees really are there to help manage rampant desire (even for good), anger and fears of premature death and disability. They were created specifically to regulate those areas. They have an impossible task and it’s salutory to learn that the first legally defined medical/research ethics committees were created in Germany shortly before WWII and theoretically had oversight of the medical “experiments” in the concentration camps. When society loses its conscience and gives in to rigid ideologies (Aryanism for example) and rampant desires (to kill, to purify, to have Lebensraum even) perhaps no structure of laws can cope.

OK, so let’s come back to questionnaires. The particular example was the fear that a student on a non-clinical degree course might use the GP-CORE to explore students’ possible distress in relation to some practical issues that might plausibly not help students with their lives, or, if done differently, might help them. The central logic has plausibility. I have no idea how well or badly the student was articulating her/his research design, I don’t even know what it was. From her/his reaction to one suggestion I made about putting pointers to health and self-care resources at the end of the online form, I suspect that the proposal might not have been perfect. Ha, there’s my superego: no proposal is perfect, I’m not sure any proposal ever can be perfect!

What seemed worrying to me was that the committee had had suggested that, as someone doing a non-clinical training, s/he should leave such work and such questionnaires to others.To me this is hard to understand. S/he will have fellow students who self-harm, some who have thoughts of ending it all. One of them may well decide to talk to her/him about that after playing squash, after watching a film together.

Sure, none of us find being faced with that, easy: we shouldn’t. Sure, I learned much in a clinical training that helped me continue conversations when such themes emerged. I ended up having a 32 year clinical career in that realm and much I was taught helped (quite a bit didn’t but we’ll leave that for now!) It seems to me that a much more useful, less rule bound, reaction of an ethics committee is to ask the applicant “have you thought through how you will react if this questionnaire reveals that someone is really down?” and then to judge the quality of the answer(s). The GP-CORE has no “risk” items. It was designed that way precisely because the University of Leeds which commissioned it to be used to find out about the mental state of its students, simply didn’t want to know about risk. (That was about twenty years ago and it’s really the same issue as the ethics committee issue.)

One suggestion from the committee to the student was only to use a “well-being” measure. Again, this seems to me to be fear driven, not reality orienting. There is much good in “well-being work”, in positive psychology, and there is a very real danger that problem focus can pathologise and paralyse. However, if we only use positively cued items in questionnaires and get a scale of well-being then we have a “floor effect”: we’re not addressing what’s really, really not well for some people. We specifically designed all the CORE measures to have both problem and well-being items to get coverage of a full range of states. The GP-CORE is tuned not to dig into the self-harm realm but it still has problems, the CORE-OM, as a measure designed to be used where help is being offered to people who are asking for it, digs much more into self-harm.

Many people, many younger people, many students, are desperately miserable; many self-harm; tragically, a few do kill themselves. Yes, clinical trainings help some people provide forms of help with this. However, improving social situations and many other things that are not “clinical” can also make huge differences in Universities. (In the midst of industrial action, I of course can’t resist suggesting that not overworking, not underpaying academics, not turning Universities into minimum wage, temporary contract, degree factories, might help.)

Misery, including student misery, is an issue for all of us, not just for some select cadre thought to be able to deal with it by virtue of a training. So too, ethics is everyone’s responsibility. Perhaps we are institutionalising it into ethics committees, into “research governance” and hence putting the impossible into those systems. We create a production line for ethics alongside the production lines for everything else. Too often perhaps researchers start to think we just have to “get this through ethics” and not really own our responsibility to decide if the work is ethical. Perhaps too many research projects now are the production line through which our governments commission the research they want, probably not the research that will question them. Perhaps that runs with the production line that produces docile researchers. It’s time we thought more about ethics ourselves, and both trusted ourselves and challenged ourselves, and our peers, to engage in discussions about that, to get into collective debugging of what’s wrong. Oops, I nearly mentioned the UK elections … but it was a slip of the keyboard, it’ll get debugged out before Thursday … or perhaps it would if I wrote still needing to be on the right conveyor belts, the right production lines.

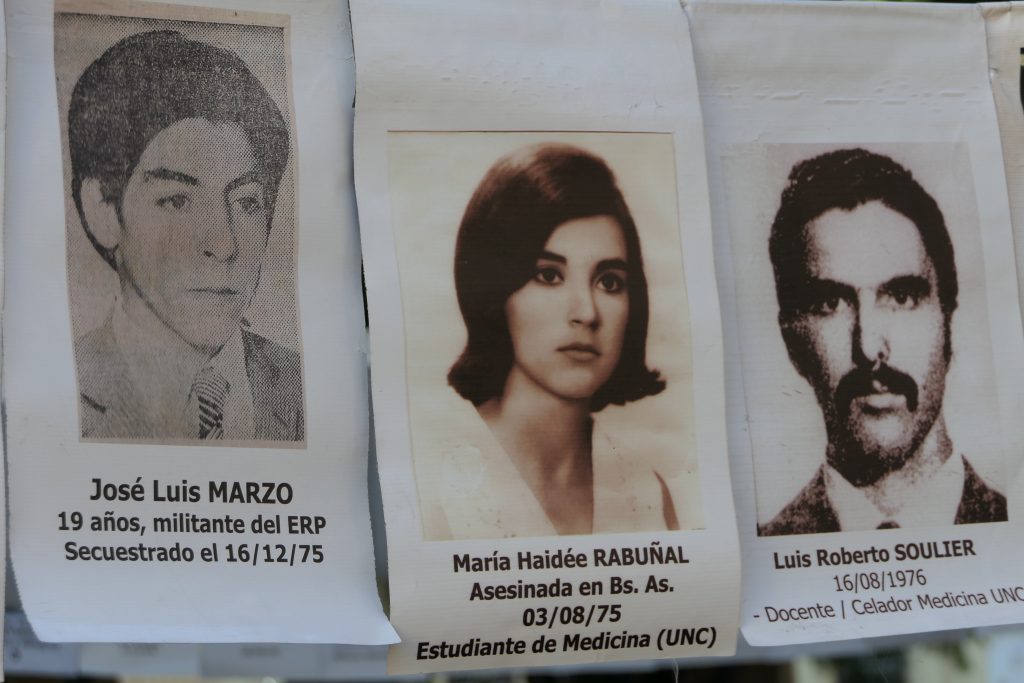

Oh, that image at the top: commemoration ‘photos, from family albums I would say, of the “disappeared” and others known to have died at the hands of the military, from Cordoba, Argentina. From our work/holiday trip there this summer. A country trying to own its past and not fantasize.